Harry

September 7 , 2025

Pan Pan* is not on an official wanted list. But about two months ago, she escaped from Myanmar to Thailand through an illegal border crossing.

She said she decided to flee after two of her friends were unexpectedly arrested by the junta earlier this year. For her, it was a sign that she could be next.

“In the early days after the 2021 coup, my friends were involved in anti-coup movements,” Pan Pan said. “But later they went back to living normal lives, just like ordinary people.”

One friend was arrested at a checkpoint in March 2025 while traveling, and the other was detained in June after staying overnight at a guesthouse, she explained.

Pan Pan believes the arrests were made possible by the junta’s digital surveillance system, particularly the PSMS technology.

“They had been living quietly in another city for a long time. They weren’t involved in any resistance anymore. But because of PSMS, they were still arrested,” she said.

PSMS — the Person Scrutinization and Monitoring System — links artificial intelligence (AI), facial recognition technology, CCTV networks, and the national citizen database, according to the Myanmar Internet Project. The system allows the military to track people’s movements in real time.

The Myanmar Internet Project was established in 2022 by a collective of researchers, practitioners and advocates with years of experience tracking developments in the Myanmar digital space.

According to Mandalay Region police records, more than 1,600 people were arrested between March and May 2025 through the use of PSMS software. This figure was reported on May 27 by the local outlet Eleven Media.

Pan Pan herself had been targeted before. In 2021, while raising funds for the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), her bank account was frozen, police raided her home, and her passport was confiscated.

“Now, if my data shows up in the PSMS system, my name will likely appear on the wanted list,” she said. “That’s why I had to run.”

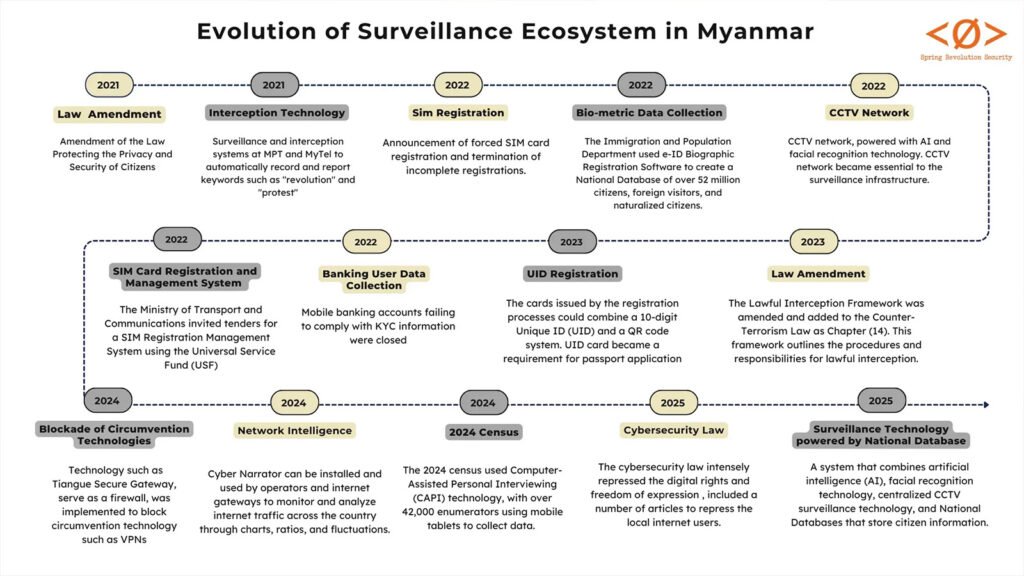

Observers say the junta has rapidly expanded its Digital Surveillance Ecosystem in the more than four years since the 2021 Military Coup. It has been strengthening the system with new technology, legal measures, and on-the-ground enforcement—largely with support from China.

Internationally, the system is known as the Person Scrutinization and Monitoring System. But the Myanmar military officially calls it the People Surveillance and Management System.

Digital rights activists compare the system to George Orwell’s classic dystopian novel 1984, in which citizens are constantly watched and denied freedom.

“In literature, the phrase ‘Big Brother is Watching You’ is symbolic. But in Myanmar today, it has become a reality,” said Thit Nyan, spokesperson for the Myanmar Internet Project.

Digital Freedoms Crushed After the Coup

When the military seized power on February 1, 2021, one of the ministries it targeted firstly was the Department of Telecommunications.

According to unconfirmed reports, when junta officials ordered phone and internet services to be completely shut down, department staff resisted. Soldiers then unplugged the cables by force. Later, military officers instructed staff to tap and report on phone calls.

A report by the Myanmar Internet Project states that shortly after the coup, automatic call interception technology was installed in the Mytel and MPT operator networks. This system automatically recorded calls containing anti-coup terms.

At that time, many SIM cards were not properly registered under real users’ names. People often used SIM cards bought under other names. Once the surveillance system was deployed, the junta forced citizens to re-register their SIM cards under their true identities.

Later, the military pressured telecom operators repeatedly to hand over users’ personal data. Researchers say that once this data transfer began, targeted arrests sharply increased.

Prominent former 88 Generation student leader Ko Jimmy (Kyaw Min Yu) was among those arrested after Norway’s Telenor handed over user data to the junta before exiting Myanmar. According to Audun Aagre, former leader of the Norwegian Burma Committee, Ko Jimmy was detained within a short time of the transfer. He wrote about the case in Panorama on August 20.

The article noted, “Telenor says they had to safeguard employee safety, despite the fact that many of the local employees in a letter asked the corporate management to ask do not disclose and leave data in Myanmar. It is very difficult to believe that they did not understand the consequences.”

Telenor handed over the data of 18 million users before selling its operations in July 2021 to Shwe Byain Phyu Group, which rebranded the company as ATOM.

Digital rights activists say that AI-driven facial recognition was later added to these CCTV networks, linked with existing smart city servers and databases established before the coup.

The Smart City program, launched under the NLD government as part of the ASEAN Smart City Network in Naypyidaw, Mandalay, and Yangon, was supported by China’s Huawei.

“This is what we call dual-use technology,” explained Ko Vox from the Spring Security Clinic, which helps address digital security challenges. “It can be used for security — but in Myanmar, it’s now being misused for control.”

Nearly 1,700 Arrests Linked to PSMS

In August this year, a leaked directive from Taunggyi Township, Shan State, General Administration Department surfaced on social media. It instructed officials to use the PSMS system to check hotels, motels, guesthouses, city checkpoints, vehicle gates, and military checkpoints starting from August 4, 2025.

According to the Myanmar Internet Prjoect’s monitoring, nearly 1,700 people were arrested from 2021 through August 2025 as a result of PSMS surveillance.

“The military now has the ability to monitor phone calls, SMS, mobile banking, facial recognition CCTV, and social media networks. It amounts to total surveillance,” said Ko Vox from the Spring Security Clinic.

Under the junta’s Cybersecurity Law enforced from July 30, digital platform companies are required to store users’ personal data for three years and hand it over directly to authorities upon request.

This means that whether people are browsing websites, ordering deliveries, renting cars, or making bank transfers, their activities can be monitored by the military, warned Thit Nyan.

To enable this level of surveillance, the junta began digitizing citizen data through an e-ID program in 2022. First, unregistered SIM cards were forced to register. Those that did not comply were shut off.

At the same time, the Ministry of Immigration and Population digitized household lists of more than 13 million families nationwide.

Officials then began collecting biometric data such as facial scans, iris patterns, and fingerprints, linking them with phone numbers. These details were entered into the national database, which now can contain the personal data of over 52 million people.

“The township offices were overwhelmed. People crowded in, and staff were exhausted. First, they collected the data of government employees as a pilot project. Later, ward and village administrators followed, registering civilians’ data,” said a person familiar with the process.

Access to this biometric database is restricted. Only government departments can connect through a dedicated VPN system. Chinese experts were involved in setting it up securely, the source added.

UID Cards and Census

In 2022, alongside the Smart City expansion, the junta rolled out additional CCTV networks in cities such as Mawlamyine, Dawei, Taunggyi, Hpa-An, and Myitkyina.

The e-ID program launched in 2022 became more visible by mid-2023, when the immigration department began issuing temporary UID Cards — plasticized cards with a 10-digit unique ID number and QR code.

Possession of a UID Card soon became mandatory to travel, cross borders, apply for a passport, or collect pensions. Local administrators pressured residents to register.

“At first, many people didn’t want to do it because they didn’t trust the military. But later, ward administrators came door to door, so most people complied. Eventually, if I didn’t, I became the only one left out, so I had to,” said a resident from Ayeyarwady Region.

For the nationwide census in October 2024, the junta announced it had used CAPI — Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing technology.

According to the Myanmar Internet Project, this data collection allowed the military to compile lists of draft-age youth, CDM staff, students, overseas workers, and resistance members.

Human rights group Fortify Rights criticized the Myanmar junta’s use of technology and call the international community to pay close attention.

“Technology in the hands of an abusive military is not neutral. It becomes a tool of control. Governments and companies must make sure they are not supporting these systems and must stand with the people of Myanmar who are demanding freedom and accountability,” Chit Seng, Human Rights Associate at Fortify Rights said.

Since the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, the junta and its affiliates have killed nearly 7,200 people, including women and children, and have arrested almost 30,000, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

“Because of all this surveillance, our daily lives feel like we could be arrested anytime on the street. Freedom of movement is gone. It’s like living inside a slaughterhouse,” Pan Pan said.

*Nickname for the safety reason

6 comments

нейросеть для рефератов нейросеть для рефератов .

нейросеть текст для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-8.ru .

реферат через нейросеть реферат через нейросеть .

умная нейросеть для учебы nejroset-dlya-ucheby-8.ru .

нейросеть генерации текстов для студентов нейросеть генерации текстов для студентов .

нейросеть студент бот нейросеть студент бот .